As one sometimes does, I was perusing EvilBay a while back and saw some ex-USSR sub-miniature pentode tubes for sale. In looking up the part number - 1Ж18Б, which is usually translated to "1J18B"(or perhaps "1Zh18B") I was intrigued, as they were not "normal" tubes.

Many years ago I'd read about the type of tube that is now often referred to as a "Gammatron" - a "gridless" amplifier tube of the 1920s, so-designed to get around patents that included what would seem to be fundamental aspects of any tube such as the control grid. Instead of a grid, the "third" control element was located near the cathode and anode. As you might expect, the effective gain of this type of tube was rather low, but it did work, even though it really didn't catch on. It was the similarity between the description of the "Gammatron" and these "rod" tubes that intrigued me.

Some information the "Gammatron" tube - not to be confused with the "Gammatron" product name - may be found at:

In reading about these particular tubes, usually referred to as "rod" tubes, I became intrigued, particularly after reading some threads about these tubes on the "radicalvalves" web site (link here) and the "radiomuseum" site (that link here). Since they were pretty cheap, I ordered some from a seller located in the former Soviet Union.

This past holiday week I managed to get a bit of spare time and decided to kludge together a simple circuit with some of these tubes. The first circuit was a simple, single-ended amplifier with one of these tubes wired as a triode. Encouraged that it actually worked, I decided to put together a simple push-pull amplifier for more power.

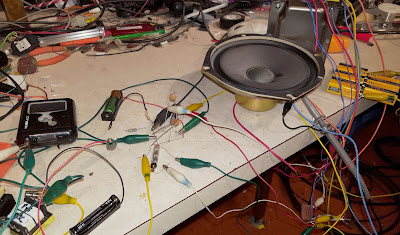

Figure 1(above) depicts the electrical diagram of the amplifier that was literally constructed on the workbench using a lot of clip leads and "floating" components as shown in the pictures. Because this was a quick "lash-up" I used components that I had kicking around with no real attempt whatsoever to obtain maximum performance.

The audio source for this was my old NexBlack audio player, designed to drive only a pair of 32 ohm headphones. To get more voltage gain to drive the tubes and to obtain the 180 degree phase split to drive the two tubes I fed the audio into one of T1's 5 volt secondaries. For the grid drive I connected the dual 120 volt primaries in series, using the middle tie point as the center-tap to which a "bias cell", a single 1.5 volt AAA cell, was connected to provide a bit of negative voltage.

Even though T1 is a simple, split-bobbin power transformer, it works reasonably well in this role. With the 5 volt to 240 volt secondary and primaries, the turns ratio is approximately 1:48 implying a possible impedance transformation of 2304-fold. In this application, the actual impedance is not important - it is only the "voltage gain" and the 180 degree phase split that we seek. In the configuration depicted in the drawing there was more than enough drive available from the audio player to drive the tubes' grids into both cut-off and saturation.

Both V1 and V2 are wired in "triode" configuration with the screen tied to the plate supply with the audio being applied to the first grid. Because these tubes' filament voltage is specified to be in the range of 0.9 to 1.2 volts, a series resistor, R1, is used to drop the filament voltage from NiMH cell B2 to a "safe" value. The plate voltage was provided by five 9-volt batteries in series with a bench supply to yield around 60 volts - the maximum rating for this particular tube.

In the same spirit as with T1, the output transformer is also one designed for AC mains use rather than, specifically, an audio transformer. In trying a number of different transformers that could be wired with a center-tap on the highest-voltage winding - including the same type as used for T1, I observed that the highest audio output power was obtained when I used the plate voltage transformer that I'd wound for a (yet to be described) audio amplifier that I'm constructing. (For an article about the construction of this transformer follow this link).

For T2, this transformer was used "backwards" with the 982 (unloaded) volt center-tapped secondary being connected to the tubes' plates. With a tone generator being used as the audio source I experimented with the various taps and windings and found that the best output was obtained across the 115 and 125 volt taps of the "primary". Based on this configuration - with 10 volts across the 115 and 125 volt primary taps - the calculated turns ratio is therefore (982/10) = 98:1 implying an impedance transformation of 9604:1. With the 8 ohms speaker, the total impedance across the entire winding is therefore calculated to be approximately 77k, or around 19k between the center-tap and each end.

Perhaps due to the "open" construction and flying leads, I noted on the oscilloscope some high-frequency oscillation on the audio output which was easily quashed with the addition of capacitors C1 and C2 on the grids of the tubes. The addition of C3 had a very minor affect, slightly improving the amplifier performance as well - such as it was!

In initial testing bias cell B1 was omitted, resulting in a quiescent current of around 6 milliamps with 60 volts on the plates. Adding this cell to provide a bit of negative bias lowered this current to around 2.5 milliamps while also improving the output power capability somewhat. Increasing this bias to about -3 volts (two cells in series) resulted in a noticeable amount of crossover distortion, indicating that too much of each audio cycle was occurring where the tube's linearity suffered and/or it was in cut-off.

In testing the audio output power was a whopping 250 milliwatts or so at 1 kHz and approximately 10% distortion while the saturated (clipping) output power was around 550 milliwatts. Referenced to 1 kHz, the -3dB end-to-end frequency response was approximately 90Hz to 12kHz with a broad 3 dB peak around 6 kHz. On the "full-range" speaker that was used for testing this amount of power was more than loud enough to be heard everywhere in the room and sounded quite good with both speech and music. If I had used a higher-power "rod" tube like the 1J37B or 1P24B and adjusted the impedance accordingly I could have gotten significantly more output power from this circuit.

While the overall frequency response performance could have been improved somewhat with more appropriate termination of transformer T1, one cannot reasonably expect the use of transformers intended for 50/60 Hz mains frequencies to provide the the best frequency response and flatness. Having said this, it is worth noting that power transformers such as that used for T1 can not only be used as a driving transformer, but it could have also been used as an output transformer in a push-pull configuration, albeit with a lower impedance. While the performance may not be ideal, their price, variety and availability make them suitable candidates for a wide variety of applications!

After satisfying my immediate curiosity about these tubes for the moment I un-clipped the flying leads, unsoldered the capacitors and put the parts away. Some time in the future I'll put together a few more "fun" projects using these interesting tubes.

[End]

Many years ago I'd read about the type of tube that is now often referred to as a "Gammatron" - a "gridless" amplifier tube of the 1920s, so-designed to get around patents that included what would seem to be fundamental aspects of any tube such as the control grid. Instead of a grid, the "third" control element was located near the cathode and anode. As you might expect, the effective gain of this type of tube was rather low, but it did work, even though it really didn't catch on. It was the similarity between the description of the "Gammatron" and these "rod" tubes that intrigued me.

|

| Figure 1: A close-up of a 1J18B tube. Note that the internals are a collection of rods rather than "conventional" grids and plates. Click on the image for a larger version. |

Some information the "Gammatron" tube - not to be confused with the "Gammatron" product name - may be found at:

In reading about these particular tubes, usually referred to as "rod" tubes, I became intrigued, particularly after reading some threads about these tubes on the "radicalvalves" web site (link here) and the "radiomuseum" site (that link here). Since they were pretty cheap, I ordered some from a seller located in the former Soviet Union.

This past holiday week I managed to get a bit of spare time and decided to kludge together a simple circuit with some of these tubes. The first circuit was a simple, single-ended amplifier with one of these tubes wired as a triode. Encouraged that it actually worked, I decided to put together a simple push-pull amplifier for more power.

Figure 1(above) depicts the electrical diagram of the amplifier that was literally constructed on the workbench using a lot of clip leads and "floating" components as shown in the pictures. Because this was a quick "lash-up" I used components that I had kicking around with no real attempt whatsoever to obtain maximum performance.

The audio source for this was my old NexBlack audio player, designed to drive only a pair of 32 ohm headphones. To get more voltage gain to drive the tubes and to obtain the 180 degree phase split to drive the two tubes I fed the audio into one of T1's 5 volt secondaries. For the grid drive I connected the dual 120 volt primaries in series, using the middle tie point as the center-tap to which a "bias cell", a single 1.5 volt AAA cell, was connected to provide a bit of negative voltage.

Even though T1 is a simple, split-bobbin power transformer, it works reasonably well in this role. With the 5 volt to 240 volt secondary and primaries, the turns ratio is approximately 1:48 implying a possible impedance transformation of 2304-fold. In this application, the actual impedance is not important - it is only the "voltage gain" and the 180 degree phase split that we seek. In the configuration depicted in the drawing there was more than enough drive available from the audio player to drive the tubes' grids into both cut-off and saturation.

Both V1 and V2 are wired in "triode" configuration with the screen tied to the plate supply with the audio being applied to the first grid. Because these tubes' filament voltage is specified to be in the range of 0.9 to 1.2 volts, a series resistor, R1, is used to drop the filament voltage from NiMH cell B2 to a "safe" value. The plate voltage was provided by five 9-volt batteries in series with a bench supply to yield around 60 volts - the maximum rating for this particular tube.

In the same spirit as with T1, the output transformer is also one designed for AC mains use rather than, specifically, an audio transformer. In trying a number of different transformers that could be wired with a center-tap on the highest-voltage winding - including the same type as used for T1, I observed that the highest audio output power was obtained when I used the plate voltage transformer that I'd wound for a (yet to be described) audio amplifier that I'm constructing. (For an article about the construction of this transformer follow this link).

For T2, this transformer was used "backwards" with the 982 (unloaded) volt center-tapped secondary being connected to the tubes' plates. With a tone generator being used as the audio source I experimented with the various taps and windings and found that the best output was obtained across the 115 and 125 volt taps of the "primary". Based on this configuration - with 10 volts across the 115 and 125 volt primary taps - the calculated turns ratio is therefore (982/10) = 98:1 implying an impedance transformation of 9604:1. With the 8 ohms speaker, the total impedance across the entire winding is therefore calculated to be approximately 77k, or around 19k between the center-tap and each end.

Perhaps due to the "open" construction and flying leads, I noted on the oscilloscope some high-frequency oscillation on the audio output which was easily quashed with the addition of capacitors C1 and C2 on the grids of the tubes. The addition of C3 had a very minor affect, slightly improving the amplifier performance as well - such as it was!

|

| Figure 4: A close up of the two tubes, flying leads, C1 and C2 and battery B2 in the background. Click on the image for a larger version. |

In initial testing bias cell B1 was omitted, resulting in a quiescent current of around 6 milliamps with 60 volts on the plates. Adding this cell to provide a bit of negative bias lowered this current to around 2.5 milliamps while also improving the output power capability somewhat. Increasing this bias to about -3 volts (two cells in series) resulted in a noticeable amount of crossover distortion, indicating that too much of each audio cycle was occurring where the tube's linearity suffered and/or it was in cut-off.

In testing the audio output power was a whopping 250 milliwatts or so at 1 kHz and approximately 10% distortion while the saturated (clipping) output power was around 550 milliwatts. Referenced to 1 kHz, the -3dB end-to-end frequency response was approximately 90Hz to 12kHz with a broad 3 dB peak around 6 kHz. On the "full-range" speaker that was used for testing this amount of power was more than loud enough to be heard everywhere in the room and sounded quite good with both speech and music. If I had used a higher-power "rod" tube like the 1J37B or 1P24B and adjusted the impedance accordingly I could have gotten significantly more output power from this circuit.

While the overall frequency response performance could have been improved somewhat with more appropriate termination of transformer T1, one cannot reasonably expect the use of transformers intended for 50/60 Hz mains frequencies to provide the the best frequency response and flatness. Having said this, it is worth noting that power transformers such as that used for T1 can not only be used as a driving transformer, but it could have also been used as an output transformer in a push-pull configuration, albeit with a lower impedance. While the performance may not be ideal, their price, variety and availability make them suitable candidates for a wide variety of applications!

After satisfying my immediate curiosity about these tubes for the moment I un-clipped the flying leads, unsoldered the capacitors and put the parts away. Some time in the future I'll put together a few more "fun" projects using these interesting tubes.

[End]